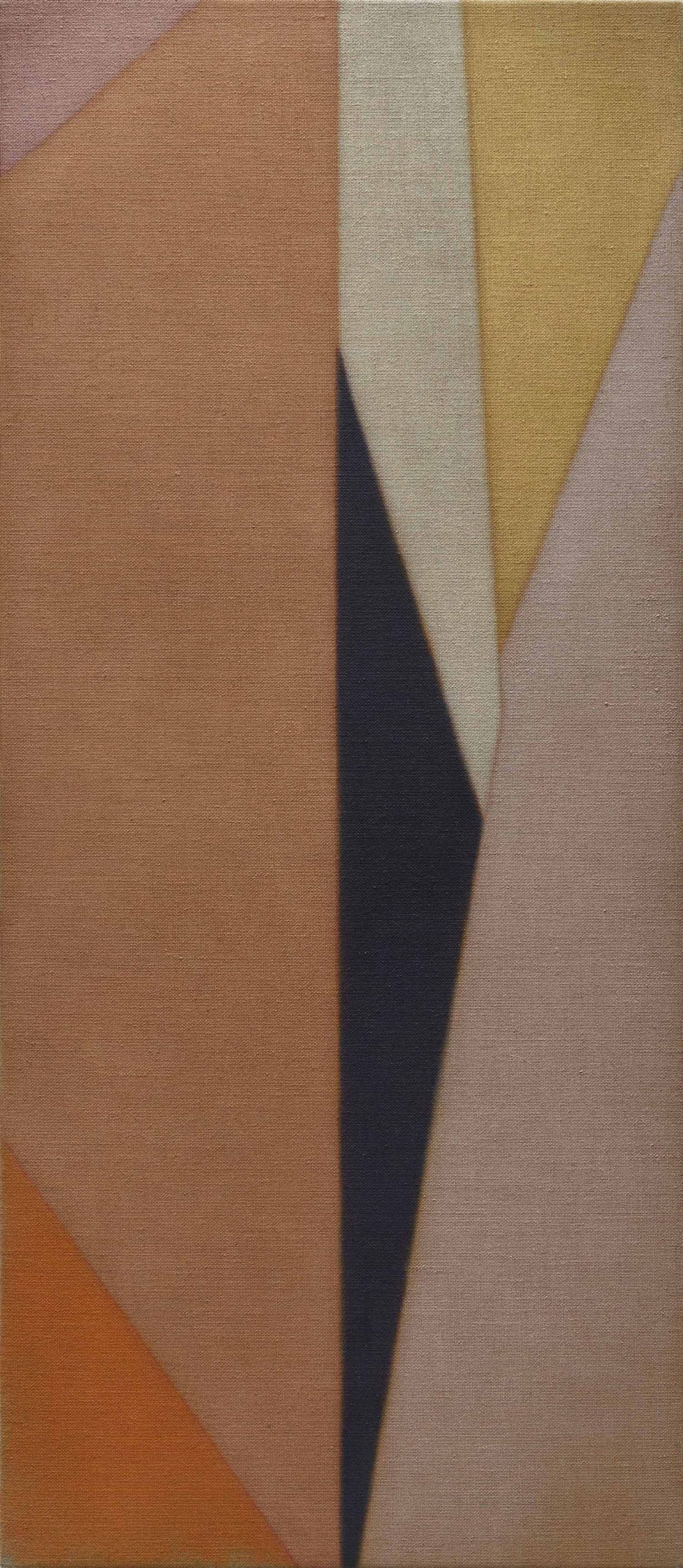

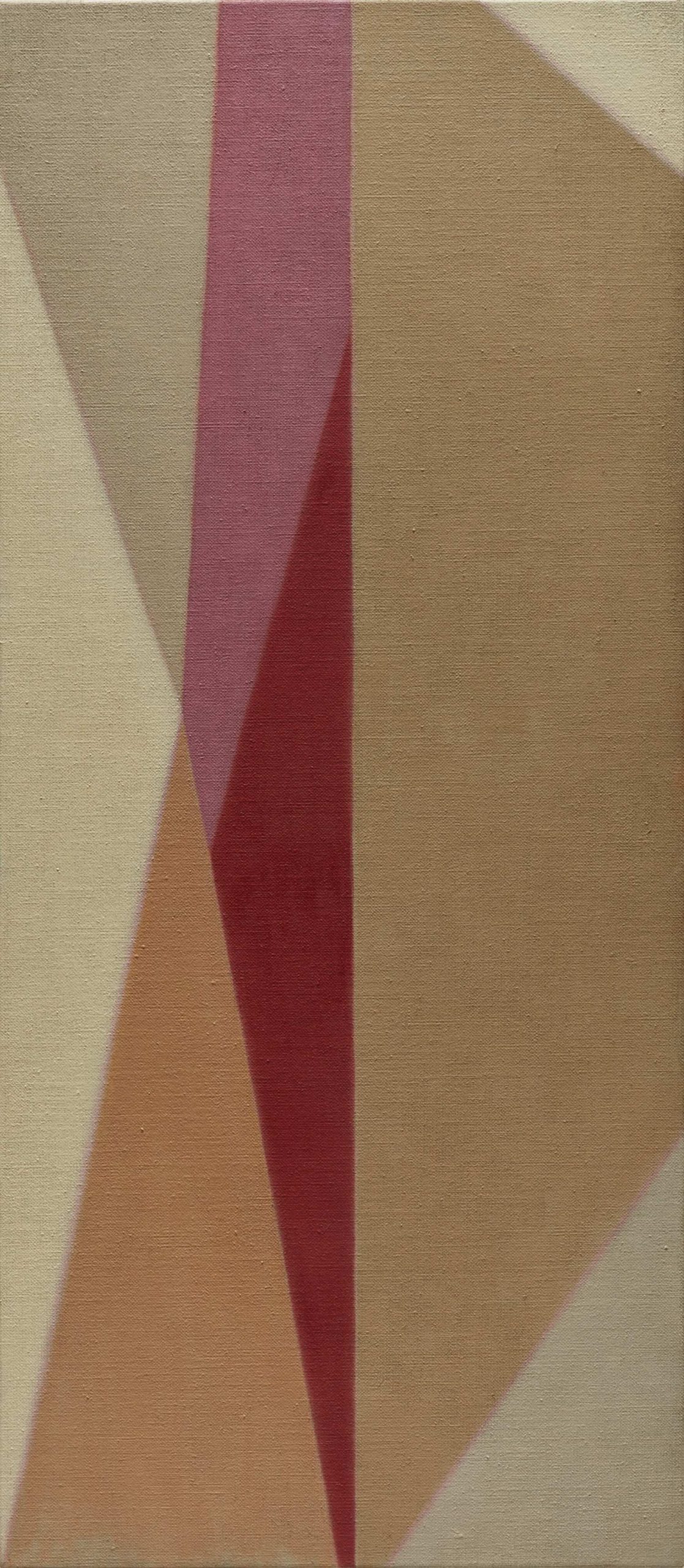

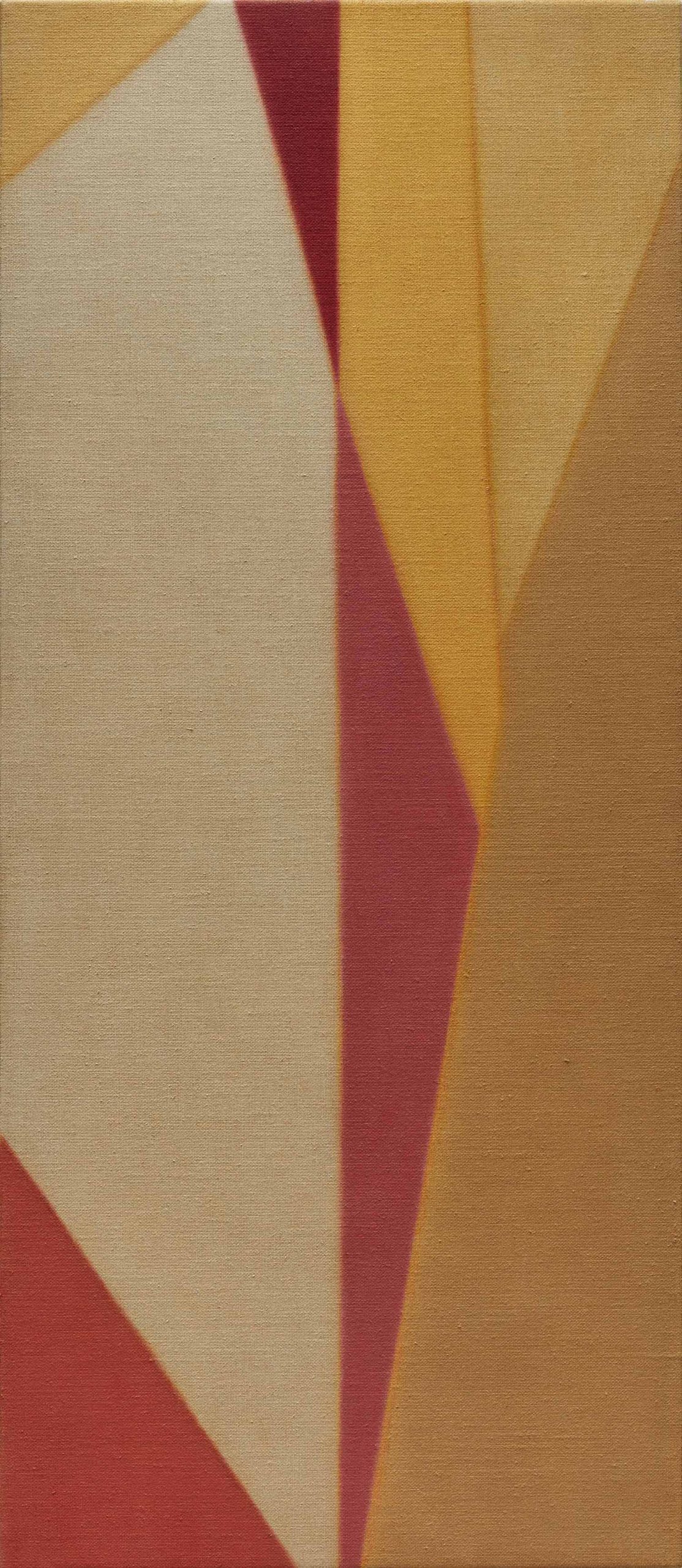

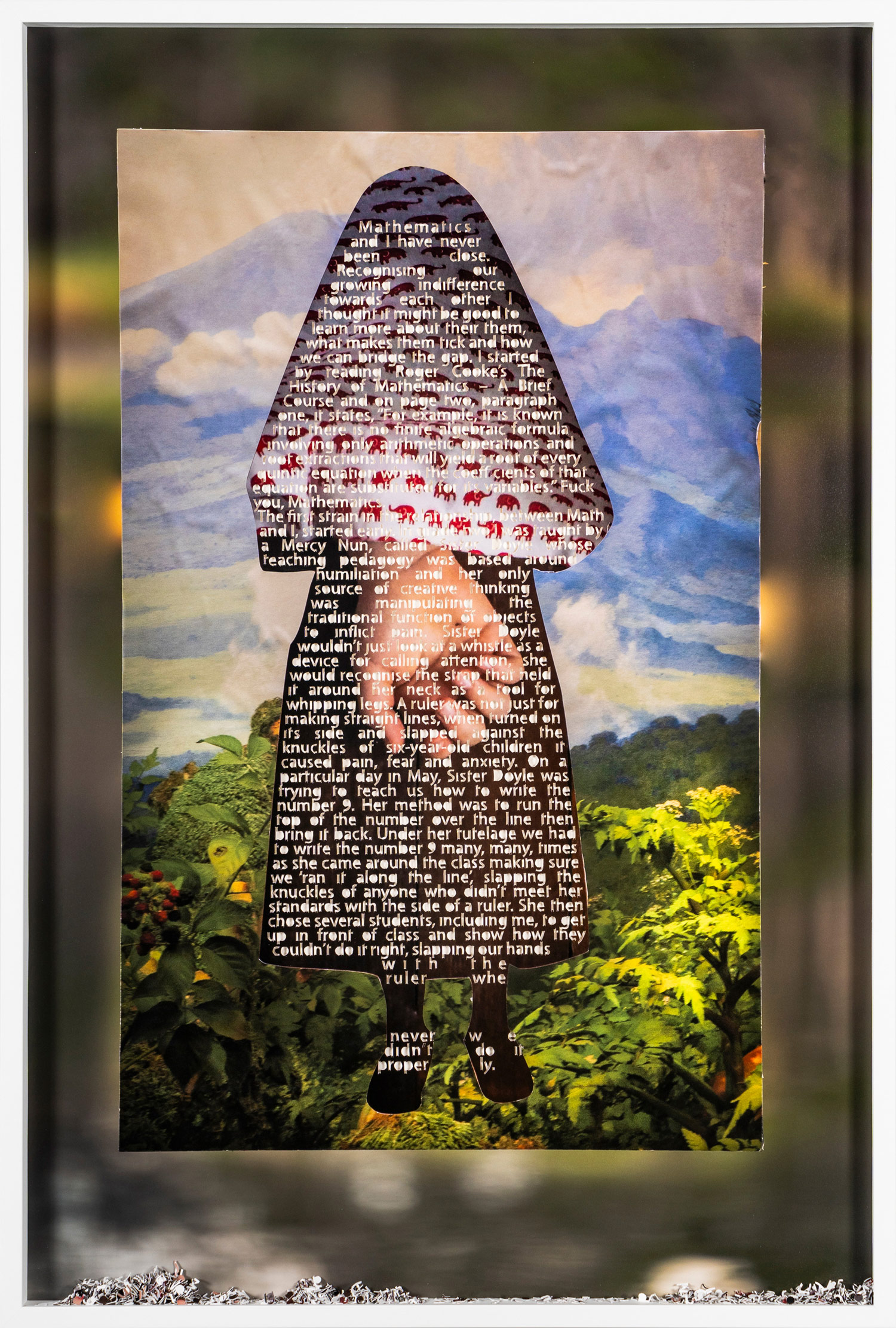

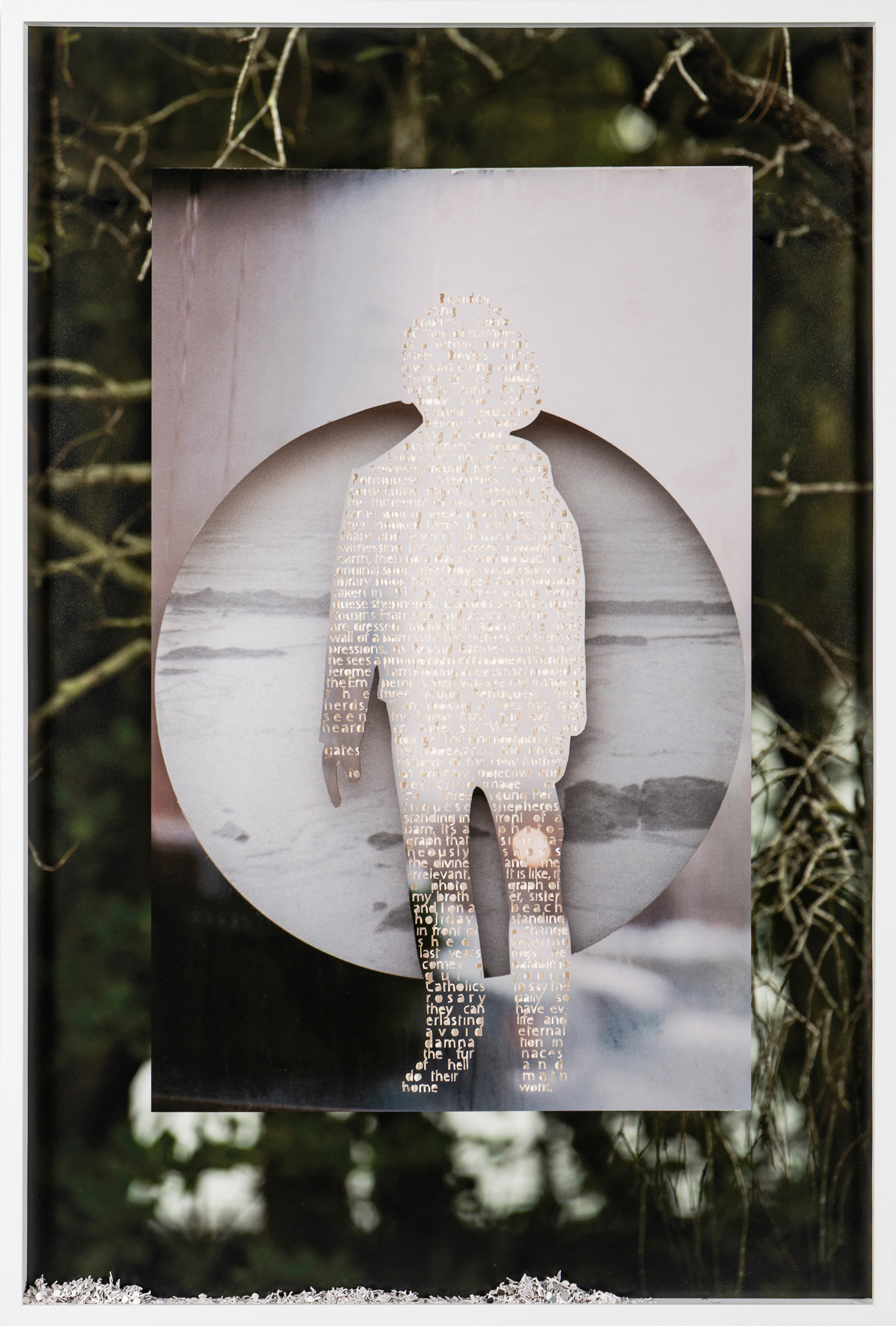

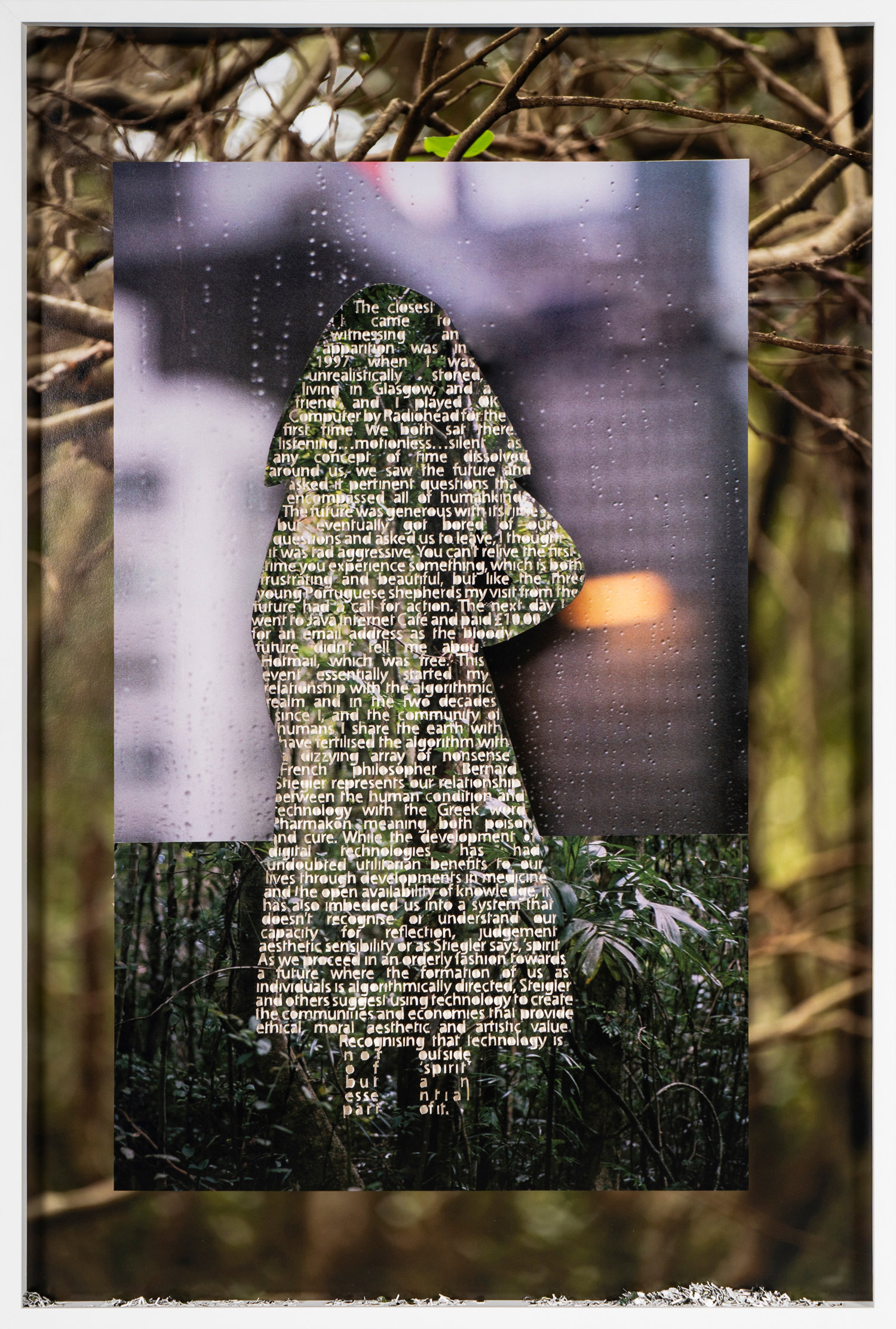

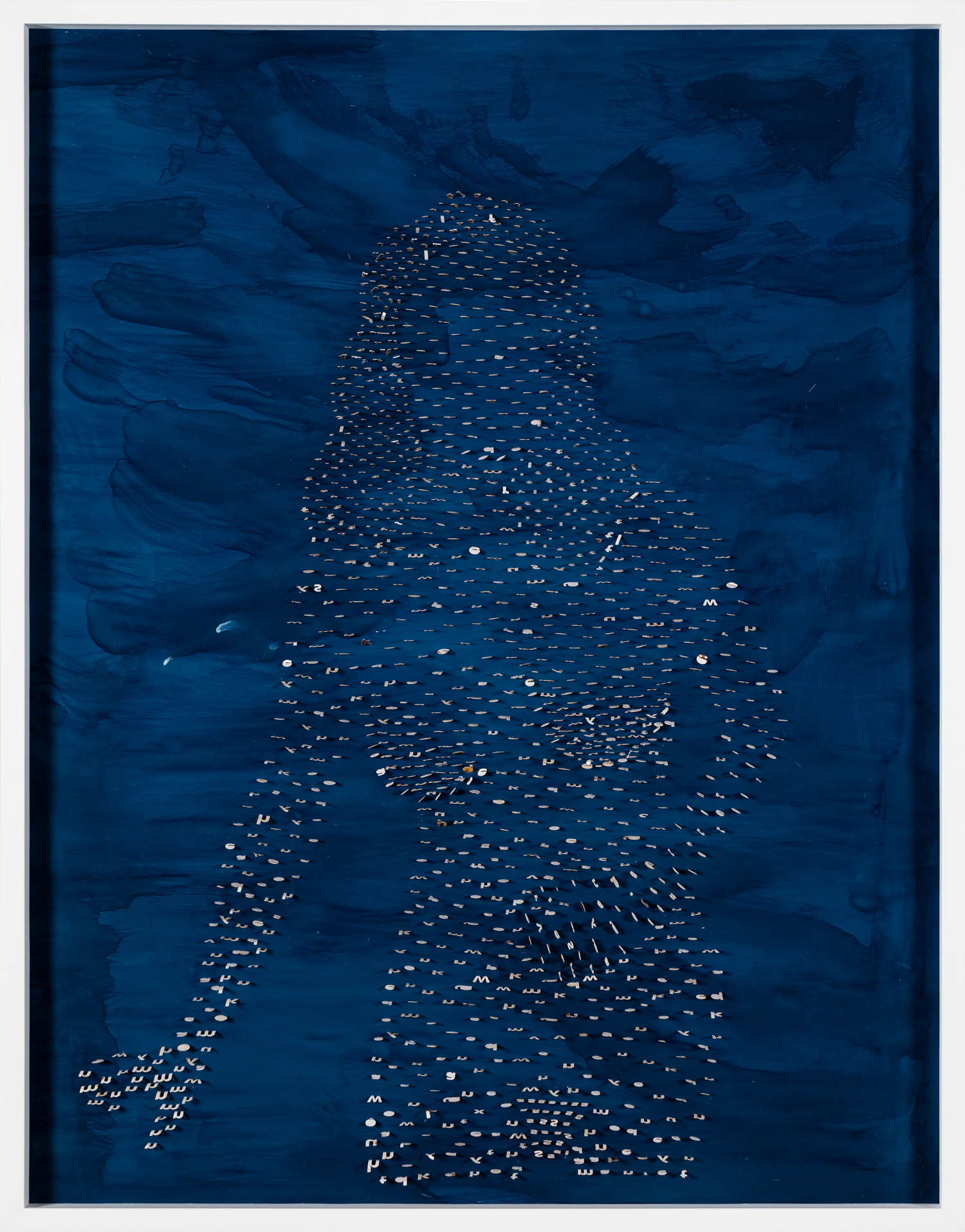

Martin Smith, Fred Fowler, Celia Gullett, Juz Kitson, Paul Davies, Monica Rohan and Adam Pyett

Jan Murphy Gallery + Sophie Gannon Gallery

Sydney Contemporary, Stand F15/F17

07 September – 10 September 2023

Click on image for artwork information